By ANTON TROIANOVSKI and SVEN GRUNDBERG

Frank Nuovo, the former chief designer at Nokia Corp., NOK1V.HE -7.36%gave presentations more than a decade ago to wireless carriers and investors that divined the future of the mobile Internet.

More than seven years before Apple Inc. AAPL -1.63%rolled out the iPhone, the Nokia team showed a phone with a color touch screen set above a single button. The device was shown locating a restaurant, playing a racing game and ordering lipstick. In the late 1990s, Nokia secretly developed another alluring product: a tablet computer with a wireless connection and touch screen—all features today of the hot-selling Apple iPad.

"Oh my God," Mr. Nuovo says as he clicks through his old slides. "We had it completely nailed."

Consumers never saw either device. The gadgets were casualties of a corporate culture that lavished funds on research but squandered opportunities to bring the innovations it produced to market.

Nokia led the wireless revolution in the 1990s and set its sights on ushering the world into the era of smartphones. Now that the smartphone era has arrived, the company is racing to roll out competitive products as its stock price collapses and thousands of employees lose their jobs.

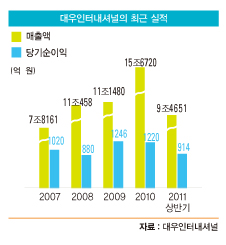

This year, Nokia ended a 14-year-run as the world's largest maker of mobile phones, as rival Samsung Electronics Co. 005930.SE -0.33%took the top spot and makers of cheaper phones ate into Nokia's sales volumes. Nokia's share of mobile phone sales fell to 21% in the first quarter from 27% a year earlier, according to market data from IDC. Its share peaked at 40.4% at the end of 2007.

Noting Nokia's History

The impact was evident in Nokia's financial report for the first three months of the year. It swung to a loss of €929 million, or $1.1 billion, from a profit of €344 million a year earlier. It had revenue of €7.4 billion, down 29%, and it sold 82.7 million phones, down 24%. Nokia reports its second-quarter results Thursday and has already said losses in its mobile phone business will be worse than expected. Its shares currently trade at €1.37 a share, down 64% so far this year.

Nokia is losing ground despite spending $40 billion on research and development over the past decade—nearly four times what Apple spent in the same period. And Nokia clearly saw where the industry it dominated was heading. But its research effort was fragmented by internal rivalries and disconnected from the operations that actually brought phones to market.

Instead of producing hit devices or software, the binge of spending has left the company with at least two abandoned operating systems and a pile of patents that analysts now say are worth around $6 billion, the bulk of the value of the entire company. Chief Executive Stephen Elop plans to start selling more of that family silver to keep the company going until it can turn around its fortunes.

"If only they had been landed in products," Mr. Elop said of the company's inventions in a recent interview, "I think Nokia would have been in a different place."

Nokia isn't the only company to lose its way in the treacherous cellphone market. Research In Motion Ltd. RIMM -2.66%had a dominant position thanks to its BlackBerry email device, but it hasn't been able to come up with a solution to the iPhone either.

As a result, the company has lost about 90% of its market value in the past five years, and its CEO is trying to convince investors the company isn't in a "death spiral."

Whereas RIM lacked the right product, Nokia actually developed the sorts of devices that consumers are gobbling up today. It just didn't bring them to market. In a strategic blunder, it shifted its focus from smartphones back to basic phones right as the iPhone upended the market.

Mobile Designs

"I was heartbroken when Apple got the jump on this concept," says Mr. Nuovo, Nokia's former chief designer. "When people say the iPhone as a concept, a piece of hardware, is unique, that upsets me."

Mr. Elop, a Canadian who took over as Nokia's first non-Finnish chief executive in 2010, is now trying to refocus a company that he says grew complacent because of its market dominance.

Shortly after taking the job, Mr. Elop scrapped work on Nokia's homegrown smartphone software and said the company would use Microsoft Corp.'s MSFT -1.79%Windows mobile operating system. By doing so, he was able to deliver a new line of phones to compete with the iPhone in less than a year, much quicker than if Nokia had stuck with its own software, he says.

Those phones aren't selling strongly. The company hasn't broken out numbers but said in April that initial sales were "mixed," and two months later said competition had been tougher than expected. Mr. Elop was forced in mid-June to announce another 10,000 layoffs and $1.7 billion in cost cuts that will fall heavily on research and development. On Sunday, Nokia cut the U.S. price of the phones in half, to $50.

Nokia has a long history of successfully adapting to big market shifts. The company started out in 1865 as a lumber mill. Over the years, it diversified into electricity production and rubber products.

At the end of the 1980s, the Soviet Union's collapse and recession in Europe caused demand for Nokia's diverse slate of products to dry up, leaving the company in crisis. Jorma Ollila, a former Citibank banker, took over as CEO in 1992 and focused Nokia on cellphones.

Nokia factories eventually sprang up from Germany to China, part of a logistics machine so well-oiled that Nokia could feed the world's demand for cellphones faster than any other manufacturer in the world. Profits soared, and the company's share price followed, giving Nokia a market value of €303 billion at its peak in 2000.

Mr. Ollila and other top executives became stars in Finland, often requesting private dining rooms when they went out to eat, senior executives said.

Early on, the CEO started laying the groundwork for the company's next reinvention. Nokia executives predicted that the business of producing cellphones that do little but make calls would lose its profitability by 2000. So the company started spending billions of dollars to research mobile email, touch screens and faster wireless networks.

In 1996, the company unveiled its first smartphone, the Nokia 9000, and called it the first mobile device that could email, fax and surf the Web. It weighed slightly under a pound.

"We had exactly the right view of what it was all about," says Mr. Ollila, who stepped down as chief executive in 2006 and retired as chairman in May. "We were about five years ahead."

The phone, also called the Communicator, made an appearance in the movie "The Saint" and drew a dedicated following among certain business users, but never commanded a mass audience.

In late 2004, U.S. manufacturer Motorola scored a world-wide hit with its thin Razr flip-phones. Nokia weathered criticism from investors that it was expending too much effort on high-end smartphones while its rival ate into its lucrative business selling expensive "dumb" phones to upwardly mobile people around the world.

After Olli-Pekka Kallasvuo, Nokia's former chief financial officer, took the helm from Mr. Ollila in 2006, he merged Nokia's smartphone and basic-phone operations. The result, said several former executives, was that the more profitable basic phone business started calling the shots.

"The Nokia bias went backwards," said Jari Pasanen, a member of a group Nokia set up in 2004 to create multimedia services for smartphones and now a venture capitalist in Finland. "It went toward traditional mobile phones."

Nokia's smartphones had hit the market too early, before consumers or wireless networks were ready to make use of them. And when the iPhone emerged, Nokia failed to recognize the threat.

Nokia engineers' "tear-down" reports, according to people who saw them, emphasized that the iPhone was expensive to manufacture and only worked on second-generation networks—primitive compared with Nokia's 3G technology. One report noted that the iPhone didn't come close to passing Nokia's rigorous "drop test," in which a phone is dropped five feet onto concrete from a variety of angles.

Yet consumers loved the iPhone, and by 2008 Nokia executives had realized that matching Apple's slick operating system amounted to their biggest challenge.

One team tried to revamp Symbian, the aging operating system that ran most Nokia smartphones. Another effort, eventually dubbed MeeGo, tried to build a new system from the ground up.

People involved with both efforts say the two teams competed with each other for support within the company and the attention of top executives—a problem that plagued Nokia's R&D operations.

"You were spending more time fighting politics than doing design," said Alastair Curtis, Nokia's chief designer from 2006 to 2009. The organizational structure was so convoluted, he added, that "it was hard for the team to drive through a coherent, consistent, beautiful experience."

In 2010, for instance, Nokia was hashing out some details of software that would make it easier for outside programmers to write applications that could work on any Nokia smartphone.

At some companies, such decisions might be made around a conference table. In Nokia's case, the meeting involved gathering about 100 engineers and product managers from offices as far-flung as Massachusetts and China in a hotel ballroom in Mainz, Germany, two people who attended the meeting recall.

Over three days, the Nokia employees sat on folding chairs and jotted notes on an array of paper easels. Representatives of MeeGo, Symbian and other programs within Nokia all struggled to make themselves heard.

"People were trying to keep their jobs," one person there recalls. "Each group was accountable for delivering the most competitive phone."

Key business partners were frustrated as well. Shortly after Apple began selling the iPhone in June 2007, chip supplier Qualcomm Corp. QCOM -1.29%settled a long running patent battle with Nokia and began collaborating on projects.

"What struck me when we started working with Nokia back in 2008 was how Nokia spent much more time than other device makers just strategizing," Qualcomm Chief Executive Paul Jacobs said. "We would present Nokia with a new technology that to us would seem as a big opportunity. Instead of just diving into this opportunity, Nokia would spend a long time, maybe six to nine months, just assessing the opportunity. And by that time the opportunity often just went away."

When Mr. Elop took over as CEO in 2010 Nokia was spending €5 billion a year on R&D—30% of the mobile phone industry's total, according to Bernstein research. Yet it remained far from launching a legitimate competitor to the iPhone.

Before the latest round of cuts, he said, the company was still struggling to focus on useful R&D. Mr. Elop has sifted through data and visited labs around the world to personally terminate projects that weren't core priorities—like one to help buyers in India link their phones to new government identification numbers.

Mr. Elop is refocusing around services like location and mapping, which came with the company's $8 billion 2008 acquisition of Navteq.

But he is having trouble rolling out products that catch on with consumers. Nokia's latest phone, the Lumia, has been well reviewed, but sales may suffer as consumers hold out for the next version of Microsoft's software, due later this year.

Jo Harlow, whom Mr. Elop appointed head of smartphones shortly after he became CEO, said Nokia will launch lower-priced Lumia devices in the coming months to better compete with aggressive Asian device makers such as China's Huawei Technologies. Ms. Harlow said the company is also "very interested" in entering the tablet market.

Mr. Elop has shaken up a sales and marketing department, replacing Chief Operating Officer Jerri DeVard and two other executives after the Lumia launch. In June, Mr. Elop picked Chris Weber, a 47-year-old former Microsoft colleague who had been running Nokia's North American effort, to take over. Ms. DeVard couldn't be reached for comment.

Nokia still is struggling to turn its good ideas into products. The first half of the year saw Nokia book more patents than in any six-month period since 2007, Mr. Elop said, leaving Nokia with more than 30,000 in all. Some might be sold to raise cash, he said.

"We may decide there could be elements of it that could be sold off, turned into more immediate cash for us—which is something that is important when you're going through a turnaround," Mr. Elop said.

Write to Anton Troianovski at anton.troianovski@wsj.com and Sven Grundberg at sven.grundberg@dowjones.com

![[SB10000872396390444873204577536780409980136]](http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/OB-TV012_0719no_D_20120719102050.jpg)

![[image]](http://si.wsj.net/public/resources/images/P1-BH101_NOKIA__NS_20120718180908.jpg)

12000 -1.2%)

12000 -1.2%) 4500 -3.2%)

4500 -3.2%)